What shared scooters in 2019 brought to Bloomington: $107K and fewer complaints

Bloomington’s uReport system for resident complaints features this item from mid-July last year: “When will the city start removing this debris?”

It was a mordant reference to the “pile of scooters” blocking the 6th Street sidewalk in front of the public library.

Complaints and comments about scooters have diminished since the Bird and Lime companies deployed them in Bloomington, starting in September 2018. But complaints have not completely disappeared. On Friday morning, @indiana_rachel Tweeted a photo of an 8-strong phalanx of Lime scooters parked in a way that blocks sidewalk passage, saying, “Hard to get past this in a wheelchair.” [Added 9:05 a.m. on Jan. 24, 2020, shortly after initial publication]

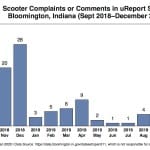

The number of complaints and comments in the uReport system is one way to track the activity of the shared-use electric scooters in the city.

Other ways include rides taken and fees paid by scooter companies to Bloomington.

Here’s a quick summary of scooter activity in Bloomington, based on UReport data, information from the mayor’s office, ridership numbers provided by scooter companies, and revenue numbers from Bloomington’s financial department:

Overview of Bloomington Scooter Activity

| 111 | uReport complaints/comments since September 2018 |

| 0 | citations for scooter law infractions |

| 378,137 | rides taken on scooters from April through December 2019 |

| $106,733 | paid by scooter companies to Bloomington |

| 3 | scooter companies licensed in Bloomington |

In 2019, about 85 percent of all scooter rides in Bloomington were taken on Lime scooters. The last row of the overview reflects the fact that Bird and Lime, whose scooters have been operating in Bloomington since late 2018, will be joined in 2020 by a third competitor in the Bloomington market.

According to Amy Hesser, director of communications for VeoRide, her company’s scooters will be deployed in Bloomington starting sometime in spring 2020.

The Square Beacon talked with Bloomington’s director of public engagement, Mary Catherine Carmichael, about the city’s future approach to enforcement of scooter laws and how revenue from scooter companies will be spent.

First up, though, is the summarized information from the overview in a bit more detail.

Complaints

Since shared use electric scooters were first deployed in Bloomington, 111 complaints or comments about scooters have been logged in the city’s uReport system. The most recent one, in early December, was a comment about a New York Times morning email newsletter that describes the “horrific” dangers that scooters pose to pedestrians.

The initial scooter deployment made caused a 3-month-long surge in uReport complaints in fall 2018, peaking in December when nearly a complaint per day was filed. A sharp drop came at the end of the year. The number of complaints grew again each month for the first four months of 2019, then dropped again to a handful per month for the rest of 2019—except for October, when 7 complaints were logged.

About 11 months after initial deployment, Bloomington’s city council enacted legislation regulating scooter use. Bloomington’s local scooter law says, for example, that scooters can’t be parked in a way that interferes with accessibility under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). That means you can’t block ramps for wheelchairs, among other things.

The new local scooter law also requires scooter companies to hold week-long twice-annual safety campaigns, during which they educate riders about the requirements of local law.

The drop in complaints could be chalked up to several factors, including the city’s educational efforts to promote better behavior by scooter reps who stage scooters at the start of the day. Another factor could be that the required scooter company safety campaigns have caused better compliance by riders when they park their scooters at a destination.

But one of those factors is not an enforcement campaign by the city. According to Bloomington’s director of public engagement, Mary Catherine Carmichael, the city has not yet cited anyone for a scooter law infraction. The legislation was enacted by the city council at the end of July and had an effective date of Sept 1.

Carmichael told The Square Beacon the city is taking more of a “carrot” approach instead of using a “stick,” so that scooter riders have a chance to learn, for example, where exactly the dismount zones are, and where scooters are allowed to be parked.

A uReport complaint from mid-October stemmed from a scooter blocking a sidewalk:

As a disabled resident of the Bloomington community I feel as if I am no longer welcome in my home. Scooters are constantly left in the middle of sidewalks, on accessible ramps and entries, and the riders zoom past without regard to the physically challenged members of Bloomington.

Asked how the city addresses such complaints, Carmichael said that if a specific circumstance is identified that can be remedied—a scooter blocking access at a specific location—then the scooter company is notified and the company sends out a representative to move the scooter.

Ridership trends

Under Bloomington’s licensing agreements with scooter companies, various data points have to be provided to the city. Bloomington has made aggregated data for scooter activity publicly available through its website.

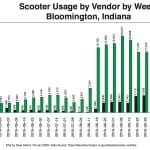

Ridership on Bird and Lime scooters for complete months in 2019 is available from May through November. For those seven months, an average of about 48,000 rides a month were taken on electric scooters from those two companies.

Fall months showed significantly higher ridership than late spring and summer months. The top month was November, when just shy of 100,000 rides were taken.

From mid-April to mid-December, the datasets show that 321,926 rides were taken on Lime scooters, and 56,211 were taken on Birds. That translates into a roughly 85-percent market share for Lime.

The number of scooters available from companies varies by day. Lime made available to potential riders an average of 300 scooters a day, compared to an average of 108 scooters a day for Bird.

Each Lime scooter was ridden twice as much on average as a Bird scooter—about 4 rides for every Lime compared to 2 rides for every Bird scooter.

That’s consistent with the average time every scooter was in use per day. Each Lime was serving a rider about 39 minutes each day, Birds about 17 minutes per day.

The data in the tables isn’t perfect. An average trip distance of 19,000 miles for one day seems implausible, for example. Cliff Ingham, the database administrator for the city who handles the scooter data, told The Square Beacon that in the raw data for each of those isolated days with implausibly high average trip distances, there’s a trip of a ridiculous length that skewed the average.

Ingham said he’ll try to get fresh data and see if the odd data is still there. One option is to delete the corrupted trip from the dataset, he said.

A plot ridership by week (from mid-April to mid-December) shows that the seasonal pattern tracks pretty close to the time when Indiana University is in session—except possibly for the two dips in November instead of one that might be expected for Thanksgiving break.

The earlier gap turns out to be a gap in the data. For Nov. 12 and Nov. 13, there’s no data in the table for Lime scooters.

The week-wise plot, as well as anecdotal evidence, suggests that scooter ridership is dominated by Indiana University affiliates. To confirm that, The Square Beacon checked with Lime, which provided some geographic perspective.

According to Russell Murphy, Lime’s communication manager for its North America East division, the majority of trips begin or end on IU’s campus.

In September there were a total of 84,988 rides. Of those 55,126 (64.9 percent) ended on IU campus. A total of 50,736 trips started on campus. It’s also not uncommon to see over 70 percent of the trips for a specific weekday end on campus, according to Murphy.

Revenue to Bloomington: What’s it used for?

Under the licensing agreement that scooter companies have with Bloomington, they pay the city 15 cents a ride. That’s in addition to a $10,000 annual licensing fee. Counting the initial $10,000 that both companies paid under an interim operating agreement, the city received a total of $106,733 in 2019.

Where does that money go? According to Bloomington’s director of public engagement, Mary Catherine Carmichael, it goes into the general fund, but it’s earmarked for expenses related to management of multimodal transportation. The expenditures need to relate to the source of the revenue, Carmichael said.

None of the earmarked scooter money has yet been spent, Carmichael said, because the city wanted to wait until enough money from scooter fees had accumulated first.

One possibility for using scooter money is to invest in additional bicycle parking spots, Carmichael said. Public bicycle hoops are one of the places where scooters can be parked.

It’s also possible to consider using scooter money to invest in scooter-specific parking infrastructure. Carmichael expressed a little caution about that possibility, saying it’s not possible to know if electric shared use scooters will be a part of the landscape five years from now. Whatever infrastructure is put in place now needs to be reversible, she said.

According to an April 2019 article in The Verge, “Ride-sharing is wildly unsustainable, and if the business continues on its current path, it’s entirely possible that these scooters will end up in a mass graveyard like those viral photos from China.”

The topic of scooters is a challenge, Carmichael said, because Bloomington has to be “nimble. That is not something municipal governments have been known for, she said.

One idea for scooter parking that’s been put on hold is to covert on-street automobile parking to parking corrals for scooter and bicycles. The delay, Carmichael said, is because of the 352 fewer downtown parking spaces the city now has, as a result of the demolition of the 4th Street parking garage. The project to replace the garage has been delayed by pending legal proceedings over the city’s related eminent domain action.

The idea of converting any on-street parking spaces to scooter corrals has been put on hold until the 4th Street garage is replaced, Carmichael said.

Scooter money could also be put into better signage to improve scooter rider behavior. On a scooter a lot of a riders’s time is spent looking down, Carmichael said, so one possibility is to put some of the messaging directly on sidewalks, instead of 12 feet in the air, where a scooter rider might not see it.

It’s an idea that’s consistent with this uReport complaint from late August last year:

… I think these signs are too high so riders don’t notice them. I didn’t realize they were there for a while. Why not lower them to eye level so they will be noticed?

Scooter money can also be used on enforcement, Carmichael said, even if enforcement is not yet the approach that Bloomington is taking.

Comments ()