When it rains, it sewers: Monday’s overflow first in 8 months for Bloomington utilities

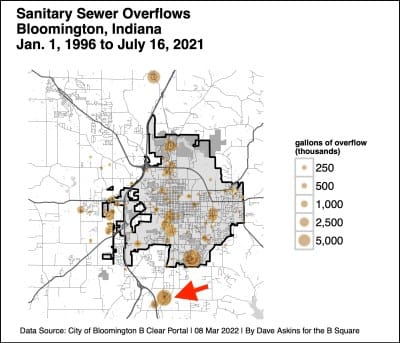

On Monday, city of Bloomington utilities (CBU) posted an alert on Facebook about a sanitary sewer overflow on Rogers Street between Charlie Avenue and Old State Road 37.

The Facebook posting advised: “Any individual who has come into direct contact with untreated sewage is advised to wash their hands and clothing thoroughly.”

What caused the overflow?

Based on a dataset maintained by the city of Bloomington, which goes back more than a quarter century, the most frequent cause of a sanitary sewer overflow is “precipitation.”

And the early-week sanitary sewer overflow at Rogers Street and Charlie Avenue squares up with the 2.15 inches of rain that fell on Bloomington on Monday. That’s the amount reported by the National Weather Service for the 24-hours ending at 7 p.m. on March 7, 2022.

What’s the connection between heavy rain and sanitary sewer overflows? And what is CBU doing about it, to prevent future sanitary sewer overflows?

The connection between heavy rain and increased volume flowing through the sanitary sewer system has received a bit of airtime over the last several months—in a somewhat unlikely context. The unlikely venue has been the regular weekly news conferences held by local leaders on the topic of the COVID-19 response.

At the news conferences, Bloomington mayor John Hamilton has reported the results of tests for gene copies of COVID-19 per 100 ml in the wastewater stream. Hamilton has sometimes provided a caveat after wet weather. The caution goes like this: A decrease in the number of gene copies per 100 ml could be due to the influx of rainwater into the sanitary sewer system, not a decrease in prevalence of the disease.

Ideally, the water that soaks into the ground when it rains should not be seeping into the sewer system through cracks and leaky pipe joints. And it’s not ideal for rainwater to be piped directly into the sanitary sewer system from a basement sump pump.

Those scenarios—called I/I (infiltration and inflow) in the wastewater treatment industry—have at least two negative impacts. First, it costs money to treat rainwater at the wastewater treatment plant. Rainwater does not need to be treated. Second, the sheer volume of the rainwater can overwhelm the capacity of the sanitary sewer pipes. That can cause untreated sewage to spill out of a manhole.

The impact of rainfall on the volume of sewage flowing into Bloomington’s Dillman Road waste water treatment plant can be seen in the daily influent numbers. At the start of February this year the daily influent number was around 11 MG (million gallons a day). After 2 inches of rain fell over two days in early February, that daily number increased to 17 MG.

Rainfall during the rest of the month pushed the daily numbers to above 20 MG, spiking to 28 MG on a couple of days.

Bloomington saw a lot of rain this February. Based on the data available for the Indiana University weather station, which goes back to 1895, the 5.66 inches of rain recorded in February this year make it the 7th wettest February in the last 127 years.

Since 1996, 738 out of 1,028 sanitary sewer overflow incidents list precipitation as the cause. Another 145 incidents don’t list a specific cause.

One approach CBU is taking to help reduce sanitary sewer overflows is to address I/I issues. That is, CBU is not trying to install bigger pipes. Instead, the idea is to reduce the amount of stormwater that makes its way into the system after heavy rains.

According to CBU director Vic Kelson, a typical I/I project involves installing a “cured-in-place-pipe” (CIPP) liner to eliminate leaks. He described it like this in an emailed response to a B Square question: “A plastic sleeve is inserted into the sewer main, and pressurized, hot air softens the plastic and inflates it to fit the inside of the pipe.”

To help fund an I/I project on the west side of town, CBU has struck an agreement with Domo Development Company, which is building the multi-family housing project at West 3rd Street. The site is just outside the Bloomington’s current city limits, but inside annexation Area 1A. That’s one of the two areas where property owners did not hit the 65-percent signature threshold in their remonstrance effort.

The $279,819 agreement with Domo was approved at the Feb. 28 of meeting of the utilities service board (USB). Domo’s project, which received zoning approval from county commissioners about a year ago, will add about 330 new apartments to the Bloomington area’s housing inventory.

Instead of upgrading the current CBU sewer pipes to increase capacity for the new development, Domo is paying towards CBU’s I/I project in the Highland Village area, which feeds into the wastewater facility at Dillman Road.

Compared to installing bigger pipes, tackling I/I is cheaper. CBU director Vic Kelson wrote in response to a B Square question, “This is a cost-effective way for us to reduce the number of sewer overflow events. It’s a ‘win’ for our customers and it’s predictable and repeatable anywhere in our system.”

As of Monday, the most recent record in CBU’s public dataset of sanitary sewer overflows showed a date of July 16, 2021. And the dataset’s metadata showed that it had not been updated since August of 2021.

According to CBU communications manager Holly McLauchlin, the apparent lag in updating the dataset is not an actual lag. Monday’s sanitary sewer overflow was the first one since July 16, 2021, McLauchlin said.

Since 1996, the overall trend for sanitary sewer overflows has been downward, both for the total number of incidents, and the estimated gallons of sewage that escaped the system.

Comments ()