Dissent from some social workers, as Bloomington’s national conference on police social work kicks off

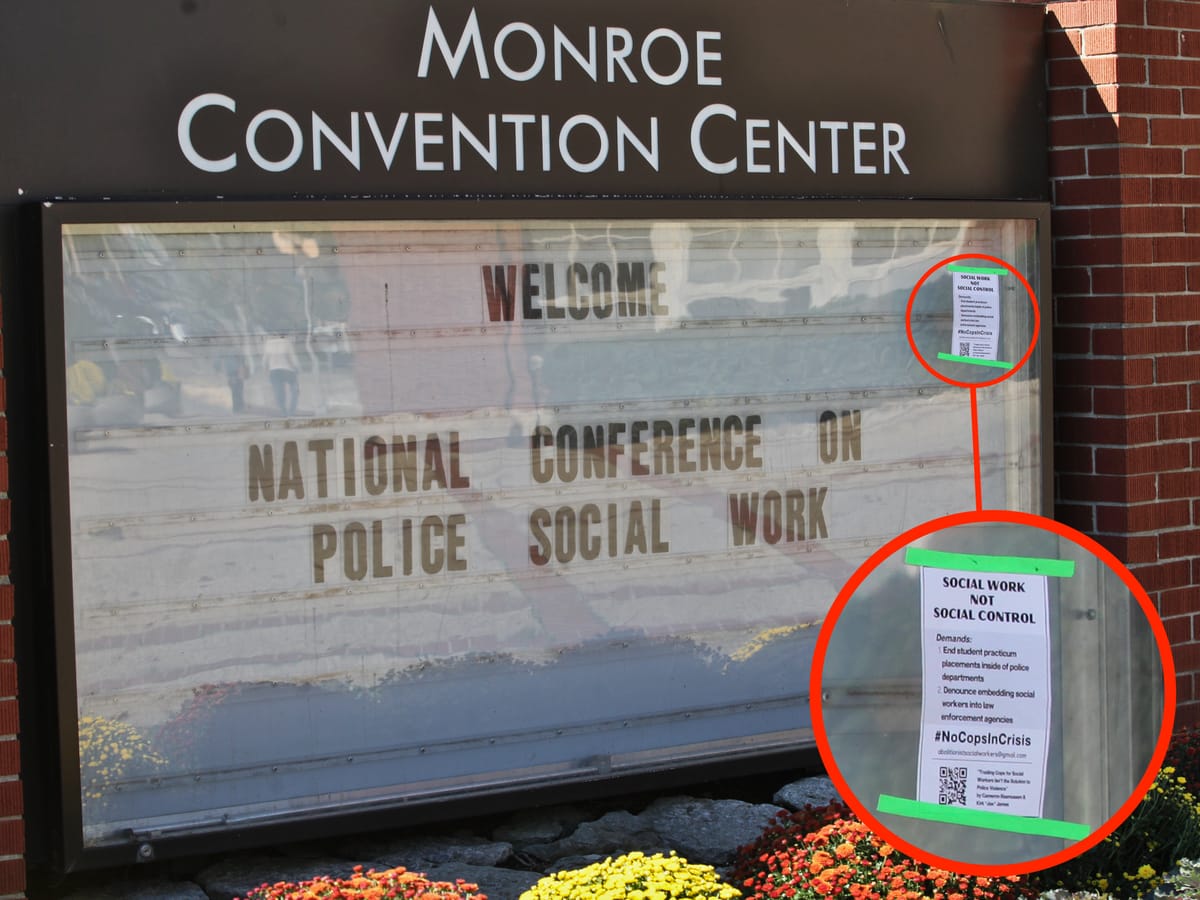

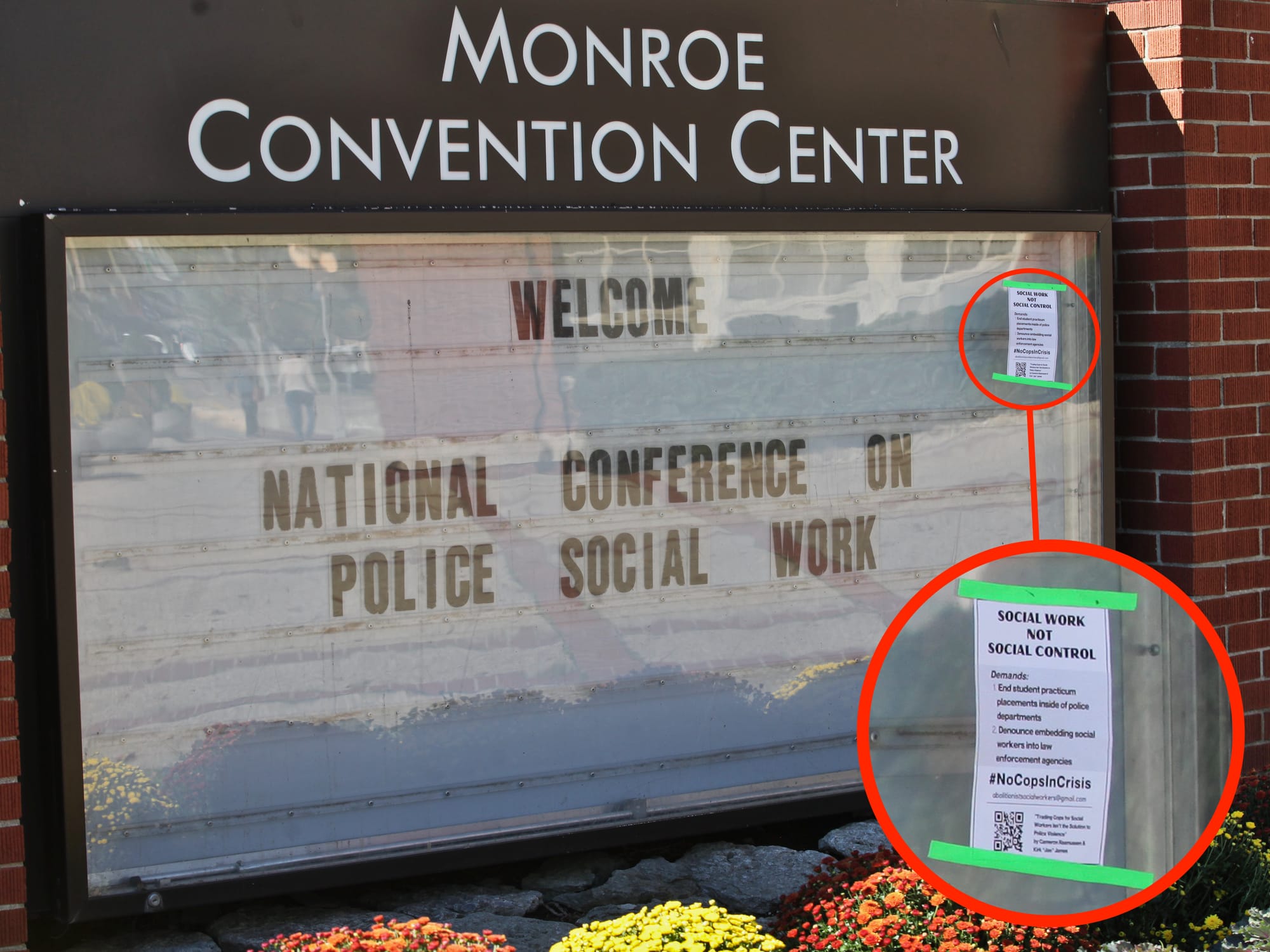

On Monday, a bit after noon, a half dozen protesters gathered at the west entrance of the Monroe County convention center.

They confronted Bloomington chief of police Mike Diekhoff as he arrived at the National Conference on Police Social Work. Diekhoff didn’t break stride as he entered the building, but greeted one of the demonstrators by name: “Hi, Alex, how are you!”

The three-day conference, which started Monday, was organized and is hosted by Bloomington’s police department. The idea that BPD would host a conference on police social work fits with the fact that BPD was the first police agency in the state of Indiana to hire a full-time social worker to be embedded in the department.

It’s the embedding of social workers in police departments that demonstrators were protesting against.

Calling themselves “abolitionist social workers,” they don’t think an organizational structure that puts social workers under the control of the police is consistent with the ethics of the social work profession. What they’d like to see abolished is policing itself.

As masters of social work student Grace Mitchell put it, as they spoke through a megaphone pointed toward the open convention center door, “There is little evidence that [social workers’] presence will reduce the disproportionate use of lethal force against Black, Latinx, or indigenous people.”

Mitchell continued, “It will not prevent [police] from patrolling certain communities over others, while serving the interests of gentrifiers, and will not demilitarize them. It will not hold them accountable for misconduct or abuse.”

Later inside the convention center, after the first day’s keynote speech, Diekhoff described to The B Square his department’s approach to asking social workers to respond to non-criminal situations. He called it a “co-response” of police officers and social workers.

Diekhoff said, “When people don’t know who to call, they call the police. We’re responding. We’re coming up with another way to respond—which is what everybody’s talking about, which is all these co-response things. That’s what this is.”

From Diekhoff’s perspective, policing has adapted over time, but the field of social work hasn’t shown the same flexibility.

Diekhoff said, “The police are all about changing and adapting. But what frustrates me is the field of social work—I don’t know that it necessarily is.”

Dieikoff added, “We’re not saying [social workers] are wrong,…But don’t criticize us as being wrong in how we do stuff, because we’re still all trying to help you.”

Diekhoff also pointed to a lot of success with the program, in the time since it has been up and running, after the first social worker was hired in 2019. Diekhoff said, “We’ve helped a lot of people. Yet, we don’t get any credit for that.”

The stats from Bloomington’s 2020 annual public safety report show that the BPD social worker spent 413.5 hours in direct contact with clients and 134 hours working on case management.

One of the demonstrators on Monday, John Loveland, a Bloomington area social worker, told The B Square, “Embedding social workers in the police department delegitimizes social workers, and legitimizes police.” Embedding social workers with police takes away the power of social workers, Loveland said.

As an alternative, Loveland suggested inverting the embedding relationship. “Let’s flip this around and make social workers in charge. And embed police with us.” That would make the chief of public safety a civilian, Loveland said—much like a civilian is in charge of the country’s military.

One of Tuesday’s conference sessions is called “The Ethics of Police Social Work,” and includes the following panelists: Carlene Quinn, associate clinical professor of social work at Indiana University: Isabel Logan, assistant professor of social work at Eastern Connecticut State University; Mallory Phagan, social worker with BPD; and Robert Madden, professor of social work at the University of Saint Joseph.

Ahead of Monday’s conference kickoff, the abolitionist social workers had already had an impact. In response to their letter of dissent, the Indiana University School of Social work announced that it would not be granting continuing education credits for attending the conference.

Two other demands made in the letter of dissent were not met: the ending of practicums for social work students in police departments; and the denunciation of the embedding of social workers in police departments.

On Monday at 7:30 p.m. the Network to Advance Abolitionist Social Work (NAASW) hosted a “counter conference” live-streamed on Instagram. On the live stream as panelists were a trio of protesters of the Bloomington event earlier in the day—Devin Wolfe, Grace Mitchell and Jacqui Cope. The Bloomington protest had started in People’s Park with sign making by maybe a dozen participants, before heading over to the Monroe County convention center.

Wolfe said Monday night, “It doesn’t really make sense to partner with an agency or a force or system that hurts the communities you’re working with, just because it’ll hurt them less. It makes more sense to just eliminate that system altogether.”

The opposition to embedding social workers in Bloomington’s police department has a history well before this week’s BPD conference. A petition was circulated in response to Bloomington’s proposed budget for 2021, which the city council approved in October 2020.

The 2020 petition, which objected to social workers inside the police department, achieved over 150 signatures. That’s more than the 10 that are the threshold, under state law, for the city council to adopt a finding on the objections in the petition.

The city council approved a budget last year for 2021 that included an additional two social worker positions for BPD, for a total of three.

In this year’s budget cycle, the city council has heard little about the question of embedding social workers in Bloomington’s police department. They have heard a lot from BPD representatives about the challenges of retention and recruitment for sworn officers.

Some councilmembers want to see money spent on base pay raises for sworn police officers, instead of hires of additional non-sworn officers. In one case, the non-sworn position would be a new deputy chief position to oversee civilian operations in the department.

Bloomington’s budget this year includes some extra drama, because the city council chose to recess its budget adoption meeting until Oct. 27, when they’re hoping for some changes from mayor John Hamilton.

But convening the national conference on police social work shows that the role of social workers inside BPD is a topic of active reflection. Diekhoff told The Square Beacon on Monday that the conference grew out of a conversation among “cops and social workers” across the country that’s been happening on Zoom once a month over the last several months.

Diekhoff told The B Square that he knows people are upset and concerned about the melding of social work and policing.

Diekhoff said when a few decades ago, when funds for mental health were cut at several levels, “A lot of that stuff fell in the laps of the police—because nobody knew who to call.”

Diekhoff continued, “You don’t see social workers stepping up, you don’t see other mental health people stepping up, and doing these types of things. So we did.”

Diekhoff wrapped up the thought by saying, “But in the end, I think both social workers and law enforcement are all about trying to help people. We’re looking for alternative ways to do so.”

Photos: Protest National Conference on Police Social Work (Oct. 18, 2021)

Click to view slideshow.

Comments ()