Bloomington goes a year without telling residents it can’t fluoridate drinking water

The city where fluoride toothpaste was invented has been unable to reliably add fluoride to its drinking water for years—and Bloomington officials never notified the public, even after they decided to forgo fluoridating the water supply while waiting for repairs.

The city where fluoride toothpaste was invented has been unable to reliably add fluoride to its drinking water for more than a year—and Bloomington officials never notified the public, even after they decided to forgo fluoridating the water supply while waiting for repairs.

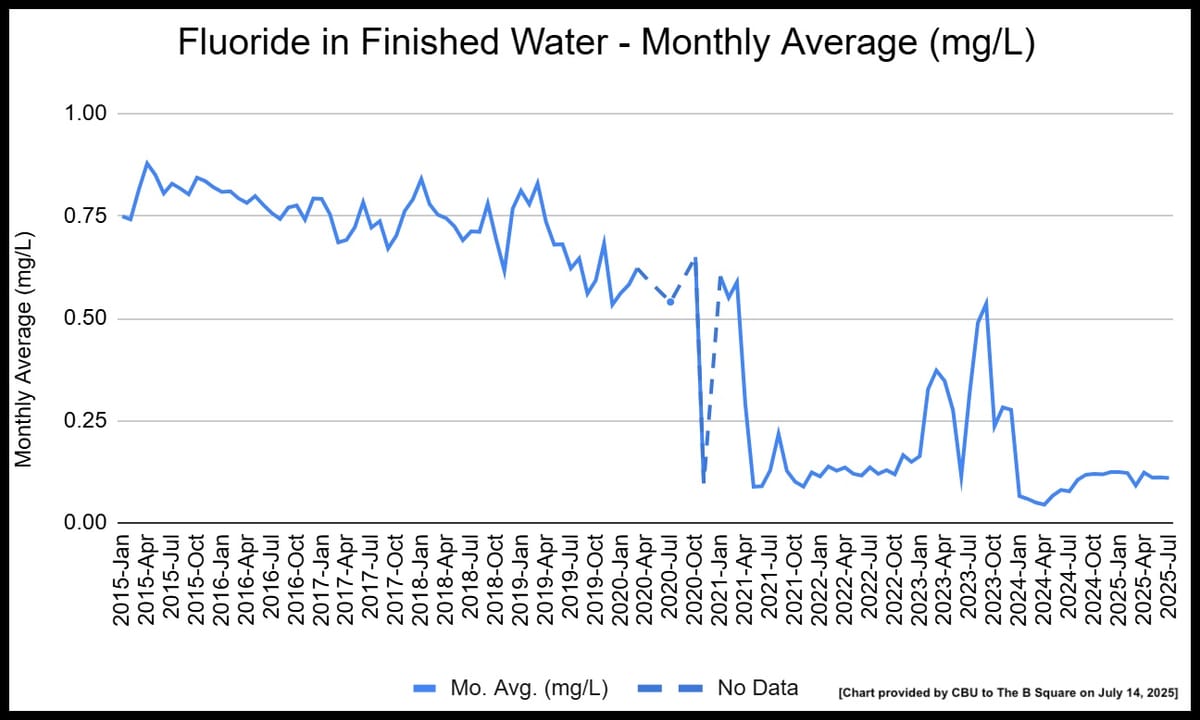

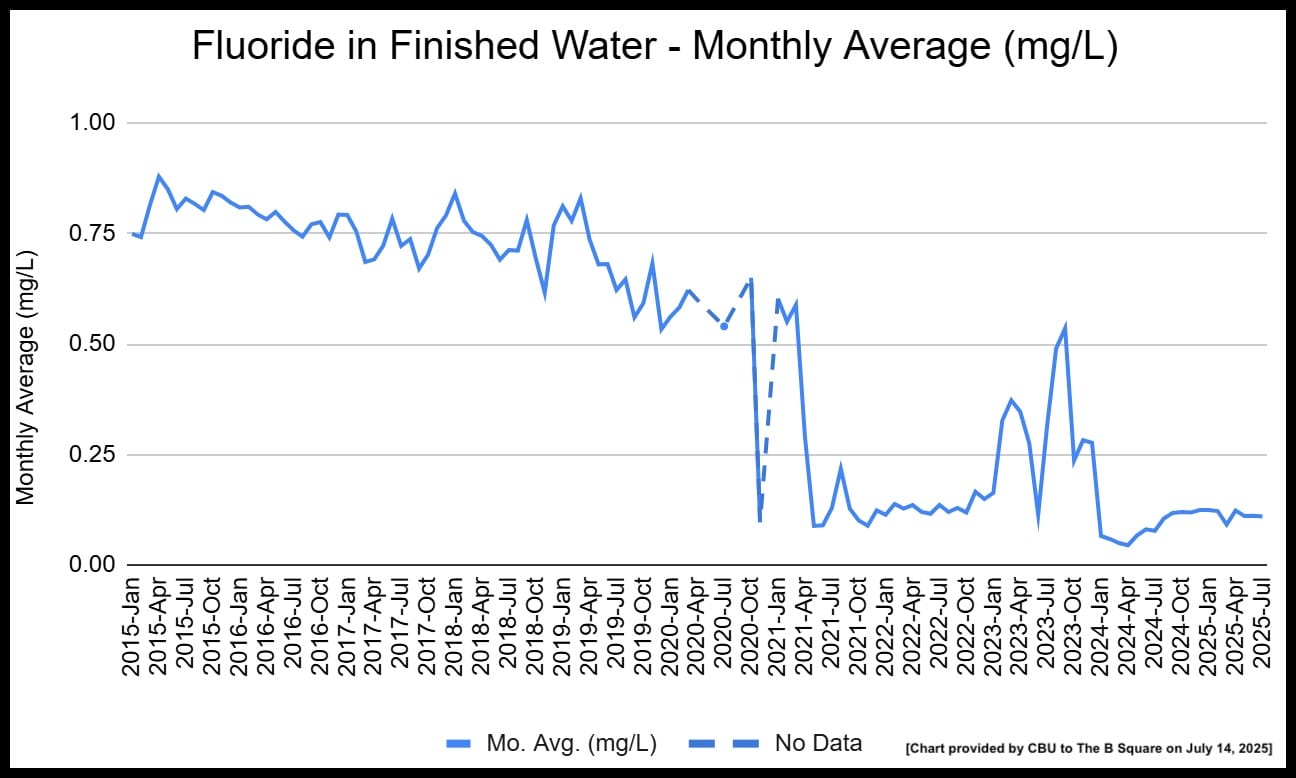

Bloomington’s monthly average fluoride levels have routinely hovered below 0.25 milligrams per liter since April 2021, well below the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommended level of 0.7 milligrams per liter.

City of Bloomington Utilities aims to restore fluoride to recommended levels by early 2026, but updates to the fluoride tank may not be completed until 2027, CBU director Kat Zaiger wrote in an email to The B Square.

Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson’s administration was first notified of the problems in June 2024, according to Zaiger. But neither CBU nor Thomson’s office ever communicated the low fluoride levels to residents or to the city council, Zaiger wrote.

Instead, the problems first became public when Indiana University chemist Katherine Edmonds read a footnote in the most recent water quality report, which was released July 2 and contains data for 2024. She noticed that fluoride content sat at 0.09 milligrams per liter—far below the recommended level.

Edmonds reached out to city officials and was told by Justin Meschter, Bloomington’s water quality coordinator, that the low levels were related to issues with the fluoride storage tank and feed system at the city’s water treatment plant near Lake Monroe. The current fluoride levels reflect naturally occurring fluoride in the reservoir, Meschter told Edmonds.

Edmonds, alarmed that residents were not notified and concerned that the fluoridation problems could harm children’s dental health, forwarded Meschter’s reply to a neighborhood email list on Friday.

“Bloomington intends to fluoridate the drinking water, but our water is not currently fluoridated and has not been for more than a year,” Edmonds wrote. “Many feel the city should have alerted us to the problem long ago and more transparently.”

City council vice president Isabel Piedmont-Smith confirmed to The B Square that she first learned of the issue on Friday via a neighborhood association’s email list.

Desiree DeMolina, a spokesperson for Thomson’s office, confirmed in an email that the office learned about the fluoride issues in June 2024 and is “planning for consistent delivery by 2026.” Asked why the city did not notify residents of the yearslong interruption, DeMolina wrote that the city felt the annual water quality report “was the most appropriate place to share fluoride levels, as it is a comprehensive tool for communicating water quality information to residents.”

But the city was already aware of the issues under Bloomington mayor John Hamilton’s administration, before Thomson began her term in January 2024. Asked for comment, Hamilton said he was first notified of problems with the fluoride feed in the fourth quarter of 2023 by Vic Kelson, who was CBU director at the time.

When fluoride levels began to dip earlier in the Hamilton administration, they were not recorded in the city’s annual water quality reports using data from 2021 and 2022.

Hamilton said the data was omitted because it was not requested from the city by the Indiana Department for Environmental Management and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which require the annual reports. Several other other Indiana localities whose reports were reviewed by The B Square did include fluoride data for those years.

DeMolina wrote that the 2025 report “was the first opportunity to restore that transparency and we prioritized including the data in full.”

“That said, we understand that residents want more than just technical reports once a year,” she added. “We’re listening and we’re committed to doing a better job of highlighting key takeaways.”

According to Zaiger, the city’s fluoride feed equipment has faced “intermittent challenges” since 2019. In 2022, the city’s fluoride tank was relined, and a smaller-capacity day tank was replaced.

Then the bulk fluoride tank sprang a leak again in 2023. A temporary system to fluoridate Bloomington’s drinking water was discontinued because it was “prone to spills and posed safety risks for staff,” according to Zaiger.

Now, the city is planning fixes to the chemical feed line later this year. City staff are currently assessing whether installing additional lining in the fluoride tanks would allow the city to restart fluoridating water in 2026. But long-term improvements to the fluoride tank are not slated to begin until 2027.

“Once that project is complete it should deliver a long-term, permanent fix and avoid the safety and operational issues we’ve encountered with temporary solutions,” Zaiger wrote.

Cities began introducing fluoride into drinking water in the 1940s to prevent dental decay. Community water fluoridation has been credited by the CDC with reducing cavities and serious dental damage by more than 25%. Excessive fluoride intake can cause tooth discoloration, and some research suggests that it may be associated with cognitive damage in young children at high concentrations—but such findings largely rely on data from areas where fluoride exposure is much higher than CDC-recommended levels.

Bloomington started fluoridating its water in 1967, but the city’s history with fluoride goes back even further. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, IU researchers developed a formula for stannous fluoride toothpaste and tested it in clinical trials on more than 12,000 local residents.

The trials showed that fluoride toothpaste reduced dental cavities, and by 1956 a toothpaste using the formula was sold widely by Crest.

But in recent years, anti-fluoride suspicion has surged—and it may be gaining institutional clout under the Trump administration. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a skeptic of mainstream science and frequent promoter of conspiracy theories, has told the CDC to reconsider its recommendation to fluoridate drinking water.

And even before Donald Trump’s return to office, some municipalities stopped adding fluoride to their water supplies. In 2021, Gosport—located in Owen County, just northwest of Bloomington—stopped fluoridating its drinking water.

When Edmonds, the IU chemist, noticed the continued low fluoride levels in Bloomington, she wondered if they could be related to political attacks on fluoridation. But Zaiger wrote in an email that the city is still committed to fluoridating its water.

“While fluoride is not considered a safety-essential chemical, the administration believes it remains an important public health measure and supports CBU pursuing a permanent and reliable solution,” she wrote.

Fluoride levels aren’t the only challenge Bloomington’s drinking water system has faced. In recent weeks, there’s been an uptick in resident complaints of yellow or brown tap water. CBU staff say the issue is related to a seasonal increase in minerals like iron and manganese in Lake Monroe and does not pose a health threat.

Comments ()