Bloomington may walk back plan to keep Kirkwood open to vehicle traffic, after city council backlash

Bloomington councilmembers sharply criticized city staff's plan to keep Kirkwood Avenue open to cars in 2026, arguing it undercuts last year’s conversion ordinance. Staff cite costs and logistics. The administration is now reconsidering the proposal and could produce a revised plan later this month.

A plan from Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson’s administration to keep Kirkwood Avenue open to vehicle traffic in summer 2026—effectively suspending the seasonal street-closure and outdoor-dining program—drew sharp criticism from several city councilmembers and downtown business owners at the council’s Feb. 4 meeting.

Economic and sustainable development (ESD) department staff say the 2025 version of the Kirkwood closure program would be “impractical” given limited resources, mixed economic impacts, and safety and accessibility concerns. From the council table and the public mic came complaints that the move flouts an ordinance the council passed last year, to give businesses multi‑year certainty and a clear path toward a more pedestrian‑oriented Kirkwood.

Based on the negative response, it looks like the Thomson administration will take some time to regroup and possibly rethink its approach. Even though the item appeared for confirmation on the original agenda for the board of public works meeting next Tuesday (Feb. 10), the updated agenda does not include the item.

In an email to The B Square, ESD department director Jane Kupersmith wrote: “City staff is taking a pause after the council meeting on Wednesday night …” Kupersmith wrote that the ESD department is now looking to the Feb. 24 meeting of the board of public works as the occasion when a “final plan” will be presented.

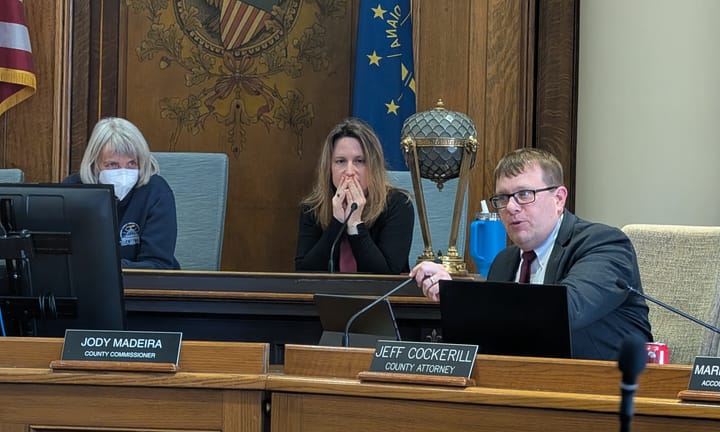

The item on Wednesday’s city council meeting agenda was not something the council was meant to vote on—it was listed as a report from the mayor’s office. The report on how the staff planned to operationalize an ordinance—approved by the city council last year on a unanimous vote—came from Kupersmith and special projects manager Chaz Mottinger.

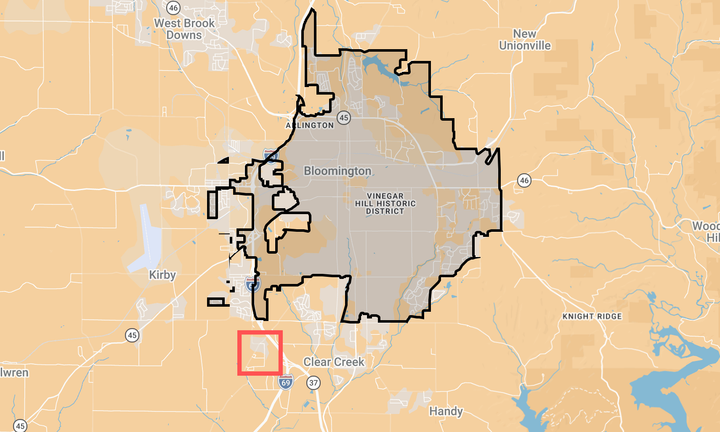

Kirkwood program presented to city council

The key features of the planned 2026 program include: keeping Kirkwood open to vehicles, thereby ending the seasonal full‑block street closures; expanding and improving parklets (on‑street dining platforms using onstreet parking spaces); shifting staff and money to “micro‑activation” events (art crawls, coffee crawls, scavenger hunts, etc.); targeting major events for street closures like Taste of Bloomington and Pridefest; and requesting funding in the 2027 budget for a Kirkwood corridor study.

Getting an implicit mention in the staff discussion on Wednesday—through reference by Kupersmith to “consultant funds” for smaller activations—was the request for proposals (RFP) the city issued last year and which was later awarded to Gather (shopkeep Talia Halliday) to serve as activation coordinator for Kirkwood. The award was not made in time to have an impact on the 2025 season.

Kirkwood was not closed to vehicle traffic in 2024, because of the major CBU storm drain project. To justify the plan not to close Kirkwood to vehicle traffic in 2026, the ESD staff report relied in part on comparisons between 2024 and 2025, when Kirkwood was closed to vehicle traffic. According to ESD staff, there was an 8% decline in average daily visits from 2024 to 2025, despite event activity that increased by 57%, and a 16% increase in program days.

Mottinger also cited problems with the 2025 closure model: business declines reported by some retailers and services; delivery and parking complications; some blocks that felt “empty” in part because they lack permanent shade and seating; accessibility and drop‑off challenges. Mottigner also pointed to an estimated $80,000 annual loss in parking revenue compared to $17,500 in program fees. Program fees are collected from businesses that want to use the street or onstreet parking spaces for dining.

City council reaction to program

That idea of not closing down the street to vehicle traffic this year for several months got a sharp response from the public mic as well as some councilmembers. The reaction was grounded partly in the wording of the ordinance enacted last year, which says that the dining program “shall operate unless earlier terminated under Section 7 of this Ordinance.”

Whether Section 7 would actually apply this year is a point of dispute—that part of the ordinance is assigned to the city engineer for their judgement. Even though ESD director Jane Kupersmith told the council on Wednesday that the engineer’s statement could be issued as soon as the following day, city engineer Andrew Cibor confirmed to The B Square on Friday he had not yet issued one.

Several councilmembers said the Thomson administration’s plan for 2026 not to convert Kirkwood to a non-motorized environment move violates the spirit—if not the exact letter—of the ordinance they passed last year. Councilmembers understood it as a commitment to keep some level of Kirkwood conversion in place for several years so businesses could plan and invest.

Matt Flaherty said that if Section 7 means that “if the administration reaches a different policy conclusion for any reason, they can go back on the ordinance, then there was no purpose in passing it in the first place.”

Flaherty framed the issue in terms of ongoing trust issues between some councilmembers and the Thomson administration: “Even if it doesn’t violate the letter of the ordinance, it certainly violates the spirit in my mind. And that’s not the first time that’s happened under the mayor Thompson administration…” Flaherty described it as part of a “pattern” and “another data point on a larger picture.”

Kate Rosenbarger said that when she spoke with ESD staff about this year’s proposal, she got the impression the decision had already been made. She questioned whether the staff could, under the ordinance, end the Kirkwood conversion, or if the staff’s role was just to develop guidelines.

Rosenbarger also questioned the focus on the parts of the street conversion that were not as successful. For some of the blocks the experience is actually “super awesome,” she said. She said, “I’ve really only heard about a few anecdotes about negative things that people think about this program, when I mostly hear positive things from members of our community. So overall, I’m like, I’m so incredibly disappointed. It’s really hard for me to even talk about.”

The first year of the Kirkwood conversion was 2020, coming out of the pandemic. Hopi Stosberg contended that there’s now a general expectation that Kirkwood will be converted to exclude vehicle traffic in the summer months: “Bloomington as a community has started assuming that it is going to be closed…” The council’s action last year was meant to help add to the stability of that expectation. Stosberg said, “I appreciate that there are some challenges related to having it closed, but I wish that we were approaching those challenges a little bit differently than just deciding not to close it.”

Isabel Piedmont‑Smith echoed Flaherty’s criticism that the decision not to convert Kirkwood to exclude vehicular traffic this year violates the spirit of the ordinance approved last year. Piedmont-Smiths said, “the administration may now be asking the engineer to come up with some engineering reason—but obviously these are not engineering reasons, most of them, for not closing the street this year.”

Piedmont-Smith also said that relying on a future corridor study risks a long hiatus for movement towards a pedestrian-oriented Kirkwood: “Corridor studies take a long time, and then you have to have the money to implement what the study says. So it can be years before we’re back on track… which I think is a track that we all agreed on at the outset, that it’s good to have this be a pedestrian space.”

Section 7: The role of the engineer

A big part of the dispute between the city council and the Thomson administration about the 2026 Kirkwood program is related to Section 7 of the ordinance enacted last year.

SECTION 7. In cases of emergency, lack of participation, or any other reason that may render the Program impractical, the Common Council authorizes the City Engineer to permanently or temporarily suspend the Program, in part or in whole. If the City Engineer suspends operation of the Program or any part of the Program, except in cases of emergency, the City shall provide notice to participating businesses no later than 14 days prior to suspension and report back to the Common Council the reasons for the suspension within 45 days of the action taken. In cases of emergency, any part or participating area of the Program may be immediately terminated. City staff shall notify businesses and City Council of the emergency termination within 72-hours of the action.

It’s the section that led to one of the sharpest exchanges of the night on Wednesday, between ESD director Jane Kupersmith, and councilmember Matt Flaherty.

Flaherty: … I think I’m understanding that the administration is saying the city engineer has determined one of these reasons to be true, which, I guess, which it is? Is it an emergency? Is it lack of participation, or is it impractical? And could you elaborate a bit on that, please?

Kupersmith: … So I think we’re looking more at the third item, where it’s rendered “impractical.” I mean, this body knows better than anyone else that we’re working with reduced resources now and going forward. I think we also learned how much in 2025…, how many resources, how much time is required to fully activate the corridor. … I think just if you need a single answer, it’s generally related to that. But in the draft memo that I saw, the engineer is pointing to the reasons outlined in the memo that was presented by ESD, which I think is multi-factorial.

Flaherty: But it’s not engineering reasons , right? Like they’re not reasons of engineering design, safety …

Kupersmith: [interrupting Flaherty] The ordinance doesn’t require engineering reasons—it says, “or any other reason that renders the program impractical.”

Flaherty: Thank you for that interpretation.

Not getting any discussion on Wednesday was the question of who actually has authority over the public right-of-way to decide closing of streets to vehicular traffic—the city council or the executive branch. It’s a question that has arisen in the Thomson administration in connection with decisions about the placement of stop signs, and the construction of neighborhood greenways.

City council president Isak Asare wrapped up the discussion on Wednesday like this: “I think it’s very clear that we want to continue having conversations and engagements on this, and perhaps in one of our deliberation sessions, we can think about action that council might want to take in this space.”

The final plan for Kirkwood in 2026 is now expected to appear on the Feb. 24 agenda for the board of public works.

Comments ()