Funding math shows Monroe County could pay for big jail and justice center, council not eager for the required tax hike

At a joint meeting, Monroe County officials confronted hard choices on a new jail: raise local income taxes to fund a $225M co-located justice center or accept a cheaper, split setup with higher long-term costs.

Left: Chief deputy sheriff Phil Parker holds up a copy of the letter from ACLU attorney Ken Falk. Looking on are sheriff Ruben Marté and jail commander Kyle Gibbons. Right: County officials gather for a joint meeting in the Nat U. Hill room. (Dave Askins, Feb. 10, 2026)

At a joint meeting Monday night, Monroe County commissioners, county councilors, judges, and the county sheriff wrestled with the task of how to move forward on a new jail amid financial constraints, political disagreement, and a looming April 15 deadline from the ACLU of Indiana.

The meeting laid bare some lingering deep frustration over the county council’s October 2025 decision to reject the purchase of the North Park site for a new jail—after three years of planning and more than $4 million already spent on studies and design work.

The meeting also brought into focus a core policy question: Is the county government willing to raise local income taxes enough to pay for a co‑located, single‑floor jail and court complex, or accept a less expensive, more fragmented solution with higher ongoing operating costs and risks?

Financing the project

Under SEA 1, enacted last year, until mid-2027 a local government can pledge only 25% of the revenue from local income tax towards a bond. In the short term, that has a severe negative impact on Monroe County’s ability to fund a new justice center and jail project,

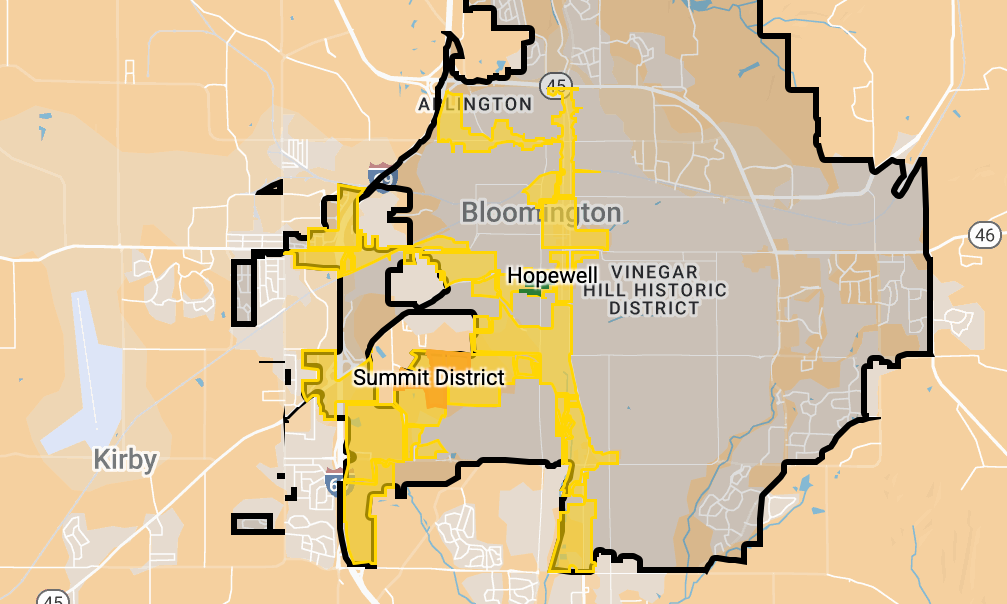

But after 2027, based on numbers presented by county attorney Jeff Cockerill on Monday, the new local income tax scheme provided by SEA 1 could provide more than enough revenue to construct the $225-million project that was planned for North Park. But that would require the county council to raise local income taxes from their current rate.

The impact of SEA 1, if it’s not modified by the state legislature this year, is that starting in 2028, all the different kinds of LIT (certified shares, public safety, economic development, jail tax, etc.) will be replaced with a single scheme that is keyed to the individual unit that can decide to impose the tax.

In this scheme, the part that was important to Monday’s discussion was the 1.2% maximum LIT rate that the county government is allowed to impose under SEA 1.

Based on Cockerill’s math, the combined effect of the 2026 local income tax collection in Monroe County translates to an effective rate of 0.86% under the SEA 1 scheme that is usable by the county government. Of that rate, 0.61 points are budgeted in 2026.

Cockerill estimated that fully bonding the previously proposed $225 million project would require annual payments of about $18 million. Just to cover bond payments for a $225-million co-located facility like the one proposed for North Park, Cockerill said Monday the equivalent rate under SEA 1 that is needed would be about 0.4%.

Added to the total rate that is budgeted for 2026 would increase the total rate that is needed to 1.01% That would mean raising the local income tax rate paid by Monroe County residents above the current effective rate of 0.86%. That would leave about 0.2 points before hitting the maximum rate of 1.2%.

Cockerill added that he thinks the county government has enough money in its current balance for the economic development fund to afford the purchase of land, without bonding.

A big unknown is whether the state legislature will modify SEA 1 to reduce a county government’s ability to impose a LIT rate up to 1.2%. One filed bill [SB 238] would have reduced that figure to 0.7%, giving cities the ability to impose a greater rate. Even though SB 238 died without making it out of the state senate, those changes could still find their way to enactment, if they are added to another piece of pending legislation.

Politics of tax increases

Councilor Kate Wiltz stressed that funding a $225-million project would mean raising local income taxes: “I just want to make sure that we’re all talking about the same thing, which is raising taxes,” she said. Wiltz added, “I just want to make it clear that that is what we’re talking about, is asking our community to pay more money to build a big jail. It’s a tough thing to sell.”

Council president Jennifer Crossley responded to Wiltz by saying, “When you say it out loud like that, that’s really hard to swallow,” Crossley said. Alluding to the council’s decision to impose a 0.17% jail tax in late 2024, Crossley said, “We already raised taxes once on people to afford this, and now to go back out again to ask for more money from people who are already strapped… that just seems like a hard ask to sell to our county residents.”

Both Wiltz and Crossley stressed they recognize the county is under legal pressure over the current facility, but want clearer understanding of what would be sacrificed—other community needs and services—if LIT is raised even more to pay for a new jail. The legal pressure stems from an ACLU decision not to extend a settlement agreement from a 2008 lawsuit past April 15 this year—unless there is clear movement towards building a new jail facility.

Judges say split courts “not feasible”

A key question running through the evening’s discussion was whether the county government can afford co‑location—keeping the jail, courts, and justice offices on a single site—or will be forced into an arrangement that is less expensive to build, with the jail separated from most court functions, but operationally more expensive in the long run.

Commissioner Julie Thomas laid out some of the issues that stem from not co-locating court functions and the jail. Thomas said that prosecutors, public defenders, probation officers, judges, and clerks would all end up “commuting between two buildings.”

Judge Catherine Stafford rejected the idea of splitting the courts between locations: “The last time the board of judges discussed the issue of whether some courtrooms could be located at a separate jail, we were firmly against it,” Stafford said.

Stafford added, “We can’t have some courts in a different location and some courts at the original location, because we don’t have our court administration there. We don’t have our court reporters there, we don’t have our recording equipment there. The cost of duplicating all of that would be extremely expensive… I don’t believe that having some courtrooms in one place and some courtrooms in another place is feasible.”

Judge Darcie Fawcett gave a practical description of why co‑location is not a mere convenience, but a functional necessity for the criminal courts, citing the daily flow of arrests, probable‑cause reviews, initial hearings, pre‑trial interviews, and the involvement of multiple offices (prosecutor, probation, public defender, clerk, and multiple criminal courts sharing duty weeks).

Alluding to the expressed need for county officials now to collaborate on the jail project, Fawcett said, “I don’t think we can collaborate ourselves out of the need for co‑location.”

Sheriff’s office: North Park rejection caused the problem

Sheriff Ruben Marté and chief deputy Phil Parker made clear that the sheriff's office has designed its operational plans around a new facility at North Park, in part to avoid repeating the mistakes of the current jail: “Everything that we’ve done so far was because of that location,” Marté said. “Everything that we try to think of was to not repeat the mistakes of the past.”

Marté warned that if the county chooses a site that can’t be expanded, it could quickly find itself over capacity and forced to pay to house people elsewhere, driving up costs again.

Parker tied the ACLU’s renewed pressure directly to the council’s October vote against the funding to acquire the North Park land. The letter that ACLU attorney Ken Falk had sent, Parker said, “wasn’t an accident.” Parker said about the letter: “That was a result of the council’s vote to eliminate North Park as a property.” Parker called that vote “an autocratic decision made by the council.”

Parker noted that more than $4 million had already been spent on North Park–related work (including design and studies), and warned that trying to find and vet a new site would likely delay the project to the point where the ACLU files a fresh lawsuit after the settlement agreement on the one from 2008 expires.

Parker said on Monday that the ACLU’s letter was distributed to every prisoner at the jail. “Now they have a voice, and they’re not going to be ignored, and they’re not going to be disregarded. I don’t think we’re going to hear a whimper from them,” Parker said.

He continued, “We’re going to hear a real loud, distinctive roar. And it’s not going to come in a meeting like this. It’s going to come in a federal lawsuit.”

Commissioners ask county council: How much?

Commissioner Julie Thomas said the commissioners need a clearer signal from the seven‑member county council, the fiscal body of the county, about its financial ceiling and its appetite for co‑location.

She asked the council to explicitly state how much LIT increase it is willing to adopt and, by extension, the project size it will fund: “What is the council willing to tax and spend to develop a facility?” Once that figure is in place, even if it is a ballpark figure, Thomas said, the conversation can start in earnest about co-location, and single-story versus multi story.

Commissioner Jody Madeira also asked councilors to identify what specifically led them to vote against the North Park location: “What features of North Park made it a no, that might make other properties also a no.”

The county council is expected to deliberate at some point at an upcoming meeting on a ballpark LIT increase that it is willing to adopt for the jail project; and corresponding funding range for construction and operations.

The first chance for that deliberation will come at the council’s regular meeting on Tuesday (Feb. 10) at 5 p.m.

Comments ()