Hopewell South PUD prompts mayor’s last-minute affordability financing proposal—could now see action by Bloomington council

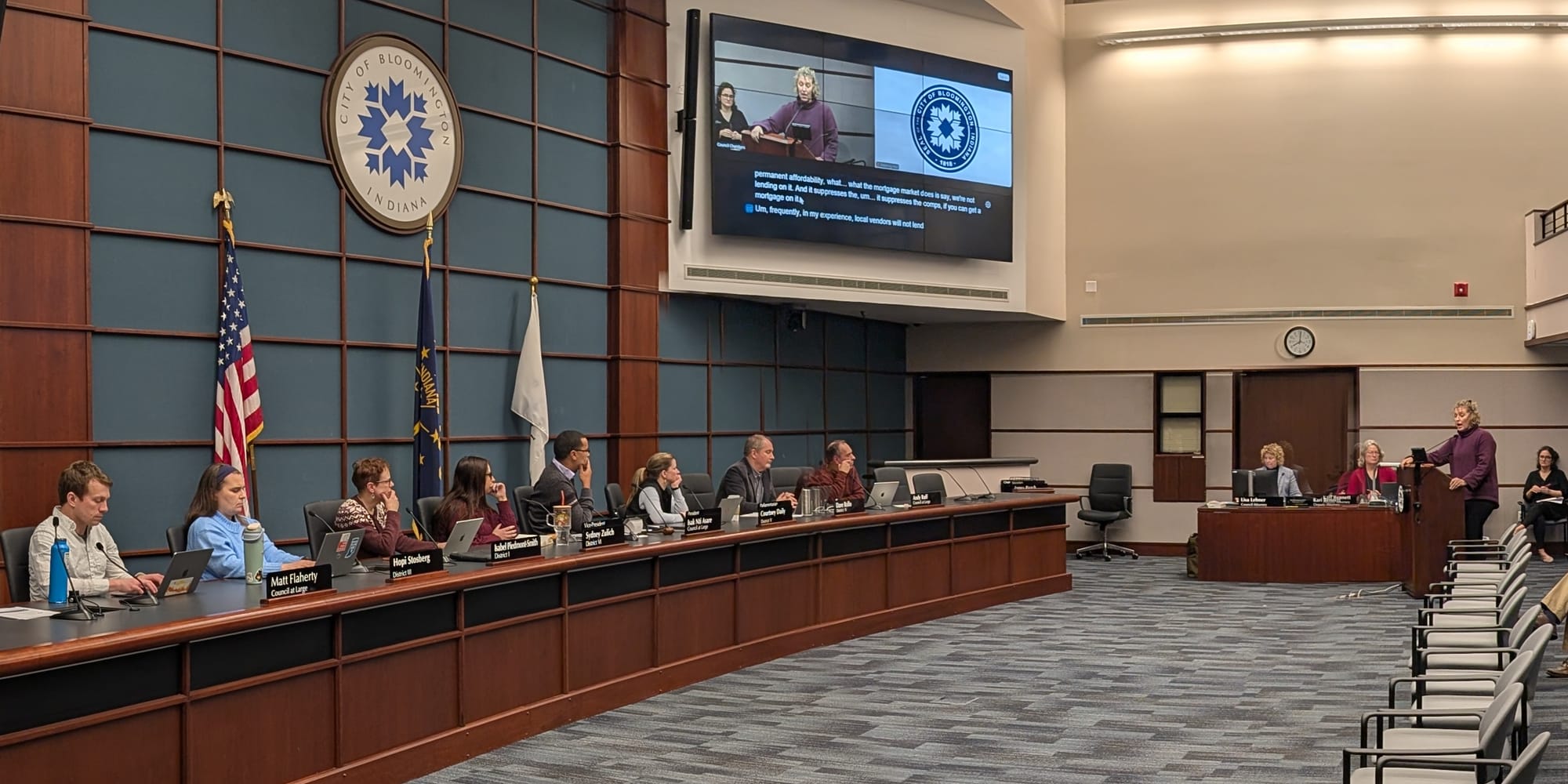

Plan commission’s Hopewell South PUD review exposed friction between “permanent affordability” deed restrictions and conventional mortgages. Two days later, city council adopted lower AMI targets for incentives (Ord. 2026-02) but delayed payment-in-lieu changes (Ord. 2026-01) to Feb. 4.

This past week’s meetings of Bloomington’s plan commission and city council offered a quick lesson in how zoning law gets made and applied.

The week’s work also illustrated how an attempt to apply existing zoning law to actual cases can almost instantly cause policy makers to wish for changes in the law. The past week’s activity by decision makers also showed how those changes can quickly get put in front of lawmakers.

On Monday, plan commissioners wrestled with a real-world test case—the proposed Hopewell South planned unit development (PUD). The Hopewell South PUD will get its required second hearing at the plan commission’s meeting next month (Feb. 9). During deliberations on the Hopewell South PUD, questions about affordability requirements collided with the practical limits of conventional mortgage financing for single-family houses.

Two days after the plan commission met, the city council took up the law itself—two ordinances that would separately amend the Unified Development Ordinance (UDO). The common thread for the two ordinances is housing affordability.

One ordinance [Ord. 2026-02] is aimed at the UDO’s affordability incentives—which already require certain percentages of the housing units to be permanently income-limited at different AMI (area median income) levels. The other ordinance [Ord. 2026-01] is aimed in part at increasing the amount required to be paid in lieu of building housing onsite, in order to achieve the affordable housing incentive.

The two meetings were tied together by a proposal from Bloomington mayor Kerry Thomson. She attended the plan commission’s Monday meeting and, based on what she heard there, asked the city council on Wednesday to consider an amendment to an ordinance that the council was already considering.

The mayor’s UDO amendment focused on making owner-occupied “affordable” homes financeable under Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac rules. But because that idea was communicated to planning staff and the council just a couple of hours before Wednesday’s council meeting, the council did not act on the mayor’s proposal.

Councilmembers put off until Feb. 4 consideration of the mayor’s idea, along with the ordinance about the payments in lieu of onsite construction [Ord. 2026-01]. It looks like the mayor’s idea will be considered as a potential amendment to Ord. 2026-01.

That’s even though the mayor’s proposal is formulated as an amendment to the other ordinance, [Ord. 2026-02 ]. The council had already considered and adopted Ord. 2026-02 at Wednesday’s meeting, before assistant planning director Jackie Scanlan presented the mayor’s idea to the council in connection with Ord. 2026-01.

Tighter AMI targets: Adopted

The main part of Ord. 2026‑02 reduces the AMI levels for Tier 1 and Tier 2 incentives, which already are a part of the UDO. A Tier 1 project can exceed the base zoning height limit by one additional floor, capped at 12 feet. A Tier 2 project can exceed the height limit by two additional floors, capped at 24 feet.

That is, in order to build taller, the developer has to make some of the units available to people earning less than the previous standards. It was assistant planning director Jackie Scanlan who presented the ordinance changes:

- Tier 1 incentives would require 15% of units to be restricted to people earning 90% of AMI.

- Tier 2 incentives would require 15% of units to be restricted to people earning a mix of below 70% and below 90% of AMI.

Scanlan said the previous 120% AMI benchmark for Tier 1 “did not reflect local income realities” and that lowering the thresholds “better captures the households we’re actually trying to serve.”

For planned unit developments (PUDs), the ordinance revises the qualifying standard so that any residential PUD must now meet or exceed Tier 1 affordability standards in the code, rather than the older 120% AMI standard.

Because the term “workforce housing” was defined in the UDO using the old 120% AMI standard, but not actually used elsewhere, the ordinance also removes that definition entirely.

Bloomington’s plan Commission had in November last year recommended the changes with a unanimous positive recommendation.

The change was not controversial—the council voted 8–0 on Wednesday to adopt the ordinance. (Kate Rosenbarger was absent.)

Payment‑in‑lieu changes: Delayed

The second measure considered by the city council on Wednesday [Ord. 2026‑01] which would alter the payment‑in‑lieu (PIL) option, was postponed to Feb. 4

Scanlan’s presentation outlined three main elements of that ordinance, which covers more than payment in lieu. The first is higher impervious‑surface caps. For single‑family detached and duplex lots in the R1–R4 districts that are intended for owner‑occupancy and meet Tier 2 affordability criteria, the maximum impervious surface could be raised to 80%.

Scanlan told councilmembers this change could allow more units or larger livable space on the same land, lowering per‑unit land and infrastructure costs. Councilmember Dave Rollo questioned the jump to 80% given the impact on stormwater management, asking how retention would handle successive rain events in the spring. That could be a sticking point for Rollo when the council considers the ordinance on Feb. 4.

A second element that would be changed by Ordinance 2026‑01 is the rules on payment‑in‑lieu (PIL) eligibility. The text would limit the PIL option to projects bigger than a certain size, with the intent, Scanlan said, of shifting more projects toward on‑site units while still leaving PIL available for larger developments. Specifically, the change would allow PIL only for projects that contain more than 30 dwelling units,.

The city’s HAND (Housing and Neighborhood Development) Department has found it harder to manage the on‑site affordability requirements, because the zoning commitments related to the requirements have not always been written to be easily enforceable.

Although not in the ordinance text itself, Scanlan previewed parallel changes that would be made to the department’s administrative manual:

- Raise the per‑unit PIL from $30,000 to $50,000 for 1–3 bedroom units.

- Add an extra $5,000 per bedroom for 4–5 bedroom units.

- Base calculations on units, not beds, and on 30% of total units rather than 15%, to better reflect the lost value of a permanently affordable unit.

Mayor’s proposal: Owner‑occupied affordability

During deliberations on Wednesday, Mayor Kerry Thomson asked the council to consider an additional amendment to the UDO, focused on owner‑occupied affordability of single family houses and mortgageability.

She said permanent deed restrictions used to guarantee affordability can make homes effectively unfinanceable: “What has been happening for a long time is when you put a deed restriction on something that says permanent affordability, what the mortgage market does is say: ‘We’re not lending on it,’” She continued by citing her background leading Habitat for Humanity of Monroe County, “If you can get a mortgage on it, frequently, in my experience, local lenders will not lend on it because it’s such a limited market that you can sell to.”

The mayor said her proposed UDO amendment essentially gives flexibility not to require a deed restriction, and so that other mechanisms can be found to ensure that the property stays affordable.

Her aim, the mayor said, is to allow other mechanisms—such as shared‑equity models with a second soft mortgage—that keep homes affordable while still allowing buyers to obtain conventional financing. Thomson said that the UDO entrenches a problem that makes owner‑occupied affordable housing difficult to build.

The mayor’s idea was born out of the plan commission’s deliberations on the Hopewell South PUD two days earlier. Hopewell South is a property owned by Bloomington’s redevelopment commission, and aims to build primarily single-family houses.

Plan commissioner member Steve Bishop zeroed in on the tension between permanent affordability and conventional mortgage finance. He flagged the fact that strong deed restrictions—of the sort the UDO currently requires for PUDs—are often at odds with how loans are underwritten and sold into the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac secondary markets. He said that if you make the restrictions too tight, you may unintentionally shut typical buyers out of mainstream mortgage products. Bishop is Bloomington Market President for First Financial Bank.

To ground that concern, Bishop pointed to Habitat for Humanity’s model. Habitat homes do carry deed restrictions, but they aren’t financed like ordinary houses. HAND director Anna Killion‑Hanson described Habitat homes as having deed restrictions that are forgiven over a period of time. That is, Habitat homes have a kind of customized workaround for the deed restrictions, because of how the secondary market treats those restrictions.

Bishop’s question to staff was essentially: Is the city going to replicate that kind of special‑case financing used by Habitat, or to use a different mechanism? Killion-Hanson’s answer underscored that it’s an unresolved issue how to make the financing possible: “I don’t know yet—we haven’t gotten there.”

The broader significance of Bishop’s commentary is that it reframes “permanent affordability” as not just a land‑use or legal question, but a capital‑markets question. If the city leans heavily on rigid deed restrictions without matching them to financing structures compatible with conventional mortgage lending the risk is that nominally “affordable” homes become practically unmortgageable for the buyers they’re intended to serve.

Next steps for Ordinance 2026‑01, mayor’s proposal

The mayor’s proposal is layered on top of the redline version of Ord. 2026-02. If the council had not already adopted it Wednesday night, the mayor’s proposal could have been treated as a straightforward amendment to Ord. 2026-02.

It looks like the mayor’s proposal got presented to the council in connection with Ord. 2026-01 only because it was added to the mix just a couple hours before the council’s meeting started.

Now, it seems like the most likely path is for the mayor’s proposal to be considered as an amendment to Ord. 2026-01. One legal question is whether the mayor’s proposal is “germane” under local law [BMC 2.04.330] to Ord. 2026-01. It seems plausible enough that it is germane to Ord. 2026-01, even if it would have been a better fit for Ord. 2026-02.

Comments ()