No fluoride added to Bloomington water: Utilities director to tell public, board of health when levels are restored

Bloomington’s drinking water has been without the recommended level of fluoride since late 2019, and city officials say it will be at least next year before the situation is resolved. But when fluoride levels are restored, the public will be notified. That’s according to CBU director Kat Zaiger.

Bloomington’s drinking water has been without the recommended level of fluoride since late 2019, and city officials say it will be at least next year before the situation is resolved. But when fluoride levels are restored, the public will be notified.

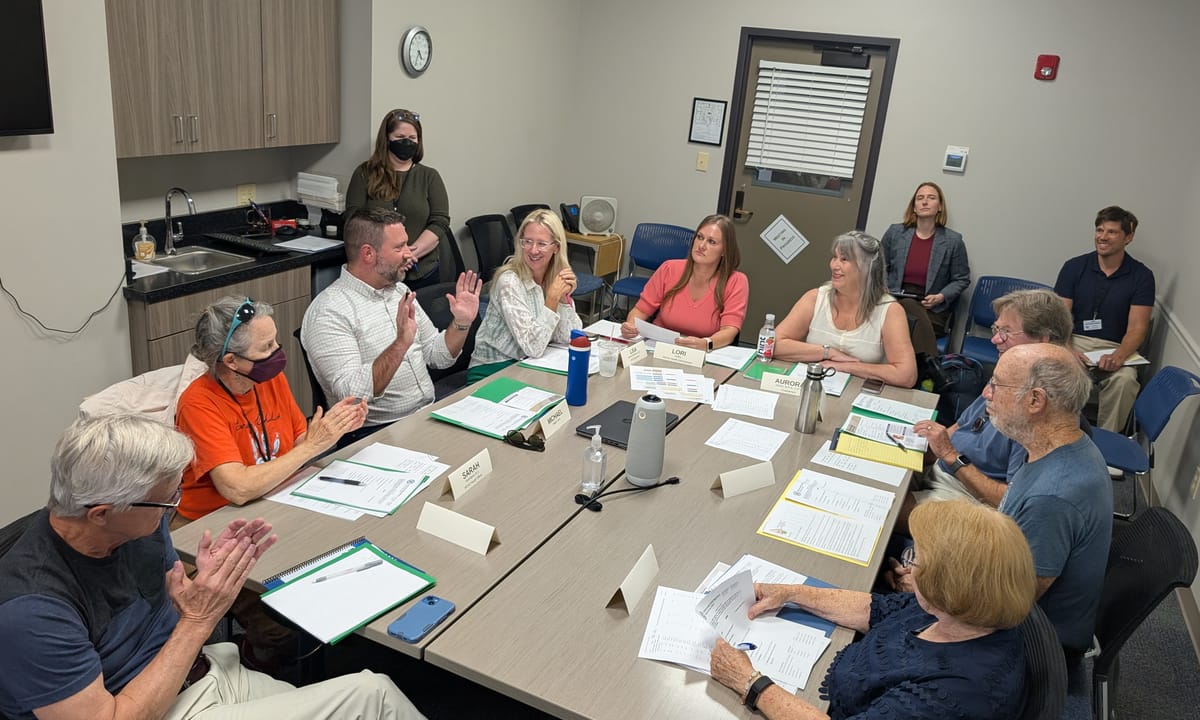

That was the message delivered to Monroe County’s board of health at its regular meeting on Thursday (Sept. 18) by City of Bloomington Utilities (CBU) director Kat Zaiger. The B Square reported on the fluoride issue in mid-July.

Zaiger confirmed that CBU is “not currently feeding fluoride” into the drinking water distribution system, citing ongoing equipment failures and safety concerns.

Zaiger assured the board and the public that when fluoride is finally added back, “we plan on making an announcement and letting folks know it’s back.”

Zaiger recounted the timeline of fluoride trouble, which started before she took over as CBU director last year, under the new mayoral administration of Kerry Thomson. The problem began at the end of 2019, when leaks developed in the chemical feed system that supplies fluoride to the city’s water.

“Our bulk tank was relined in 2022 from a leak, but it continued to leak after that,” Zaiger said. Temporary delivery systems were tried, but these posed “significant safety risks to staff,” she said, because the hydrofluorosilicic acid used for fluoridation is “one of the most dangerous chemicals we have at our plant.”

Currently, the city is testing whether further relining of the 20-year-old tank will be effective, while also exploring other options. Zaiger said the goal is to have a “safe, temporary, cost-effective solution finished by the beginning of 2026,” with a more comprehensive overhaul planned for 2027.

Describing the temporary solutions, Zaiger offered an analogy from her past as a bartender: “That temporary solution looks like a tote, and that tote is hooked up to a pump. … You would change a keg, and you would put that tap in and sometimes it’d spray out.” Zaiger told the board that the spray from the chemical-filled tote didn’t happen every time, but it was always a possibility, which meant that it was a safety concern.

Zaiger stressed to the board that, despite the lack of added fluoride, the water remains safe to drink. “The presence or absence of fluoride, while still [a] public health issue, does not have an impact on the potability of our water and the safety of our water.”

Reacting to the idea of a publicity push about the lack of added fluoride, Zaiger said those types of notifications are reserved for safety issues related to drinking the water: “Is your water safe to drink right now?” About Bloomington’s current situation with drinking water, Zaiger said, “Even though it is not as awesome without fluoride, it is still safe to drink.”

Board of health member Stephen Pritchard, a retired dentist, expressed dismay that the dental community had not been notified about the lack of fluoride in the last five years when the problem started. “This is a serious public health issue,” Pritchard said.

Pritchard added, “Low-income people are disproportionately affected because they may not take their kids on a regular basis to the dentist. It’s only 40% of the people [who] go to the dentist anyway.” Because dentists were not aware of it, they were not in a position to recommend to their patients ways to compensate for it, with topical fluorides at home, Pritchard said.

Pritchard put it like this “If this problem’s been going on for five years, that’s a whole set of … primary teeth on one child that maybe had no fluoride.”

Pritchard also criticized the way fluoride levels have been reported in the city’s annual consumer confidence report, saying the focus on maximum readings was “misleading” and that average levels would be more informative.

Zaiger acknowledged the communication gap, noting that for two years before she became director, fluoride levels were not included in the annual report at all. “We put it back in our report because we thought it was the right thing to do. We should have probably done more push in education,” she said.

In response to concerns about communication, Monroe County health officer Sarah Ryterband suggested that a resolution could be adopted by the utilities service board (USB) that would say something like: CBU will notify the county board of health when fluoride is either absent or comes back on line in the drinking water.

Zaiger told Ryterband that as utilities director, she could simply implement that without a resolution. But Zaiger added that a USB resolution could help ensure that future directors have a reference point.

For now, the city’s water contains only naturally occurring fluoride at about 0.1 milligrams per liter—well below the recommended 0.7 milligrams per liter. The earliest a temporary fix could be in place is 2026, with a permanent solution not expected until 2027.

Comments ()